Learning unfolds as a series of abstractions that grow increasingly complex - each stage builds on previous concepts while providing new ways to look at the same subject.

First we learn the alphabet, then we learn words, then we string together sentences, cobble together patchwork paragraphs, and still beyond we may assemble them into whole essays, books, scripts or some more complex form.

At each stage, we chunk our understanding in ways that open our eyes to patterns we could not discern before. Famously, expert chess players perceive board states as entire groups of pieces, rather than isolated individuals.1

Since working on our game, Skadi Tower, over the last few years, I've developed my own understanding and way of visualizing the puzzles. A series of abstractions and quickly calculated heuristics tell me at a glance whether a level is solvable or not. I've noticed the gap in the way I see the puzzles after our extensive playtesting. Observing new players, reveals when they have yet to internalize the logic and rules of the puzzle system. On the other hand, returning players or those with experience in line puzzles blaze past the early levels.

I offer you the perspectives I’ve gathered on our puzzles across the time I spent poring over the design of our game.

I.

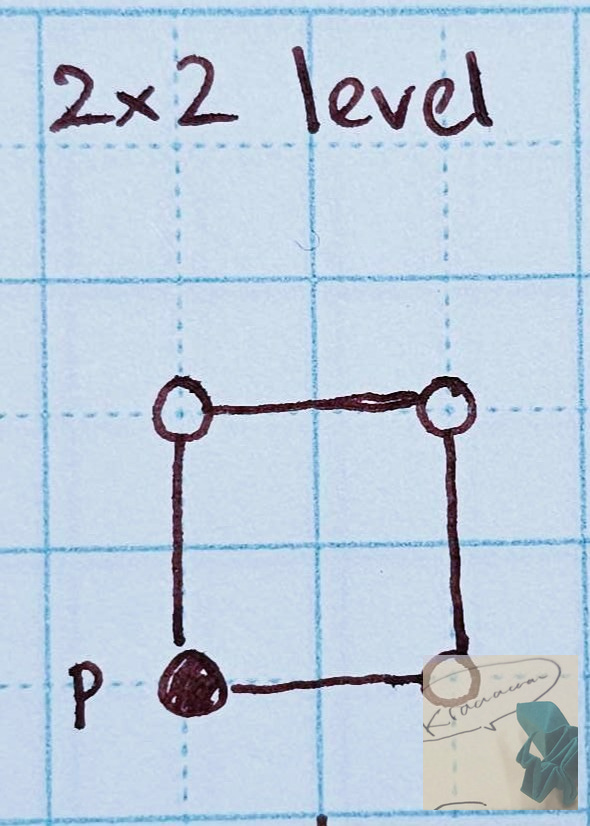

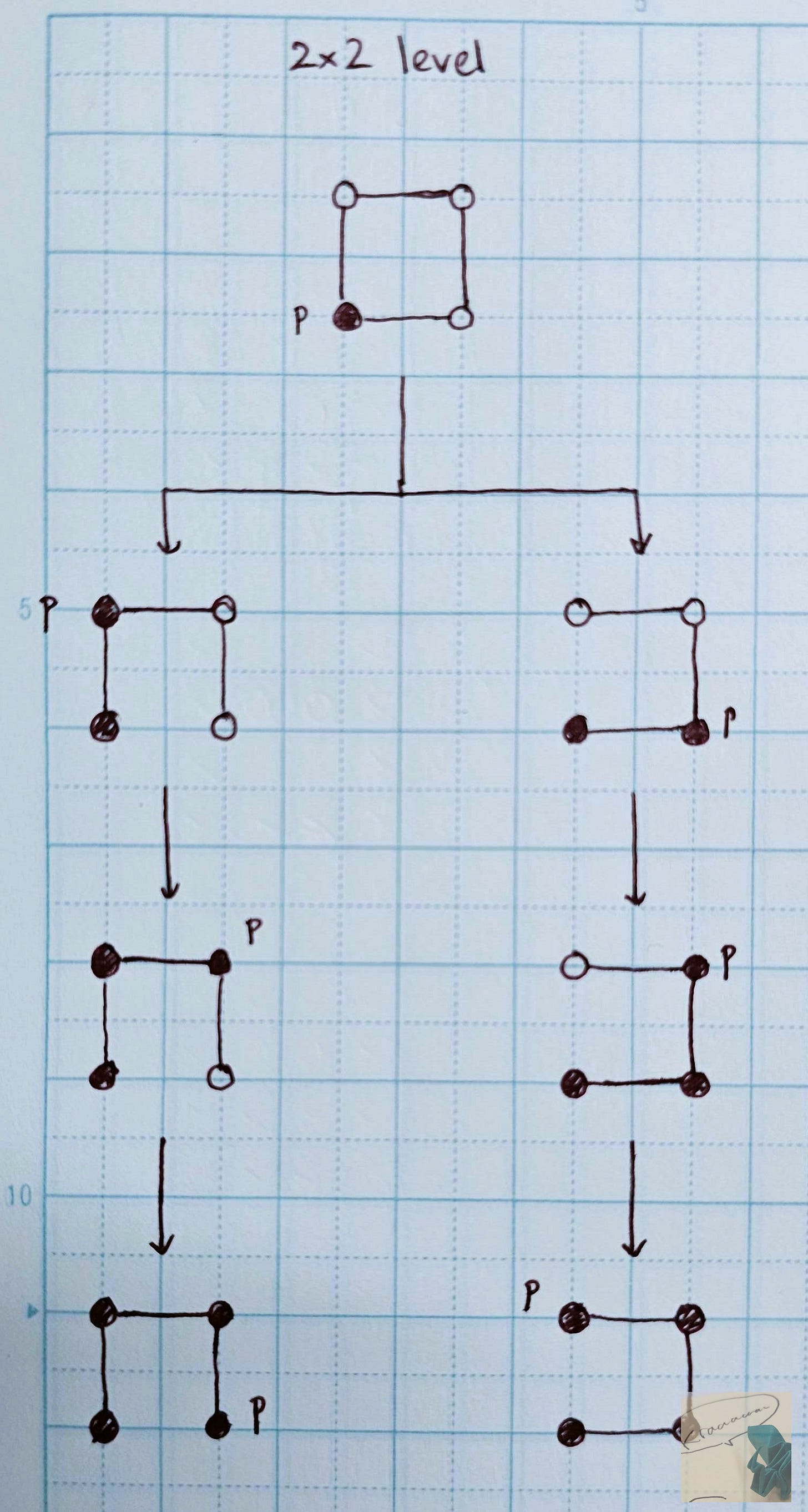

Let's start with a simple puzzle - a 2x2 grid of ice tiles.

For every ice tile, we will draw a circle (i.e. an edge) and then we will connect each circle to its orthogonal neighbors using lines (i.e. vertices). Let's also mark the tile the player is starting on with a 'p'.

From here, we will explore every possible move the player can make using a flowchart of the game states visually. After each move, we will shade in the tile that has been walked on and stop drawing the lines (edges) we cannot move along anymore.

I want you to notice two key points:

(i) On the first move, I had a choice of moving up or moving right

(ii) After the first move, my choices didn't matter because there was only one allowed path to complete the puzzle, in either case. Let's call the solution from this point on as 'trivial'.

The more we play, the earlier we can recognize a shape/area of ice tiles that have a trivial solution.

II.

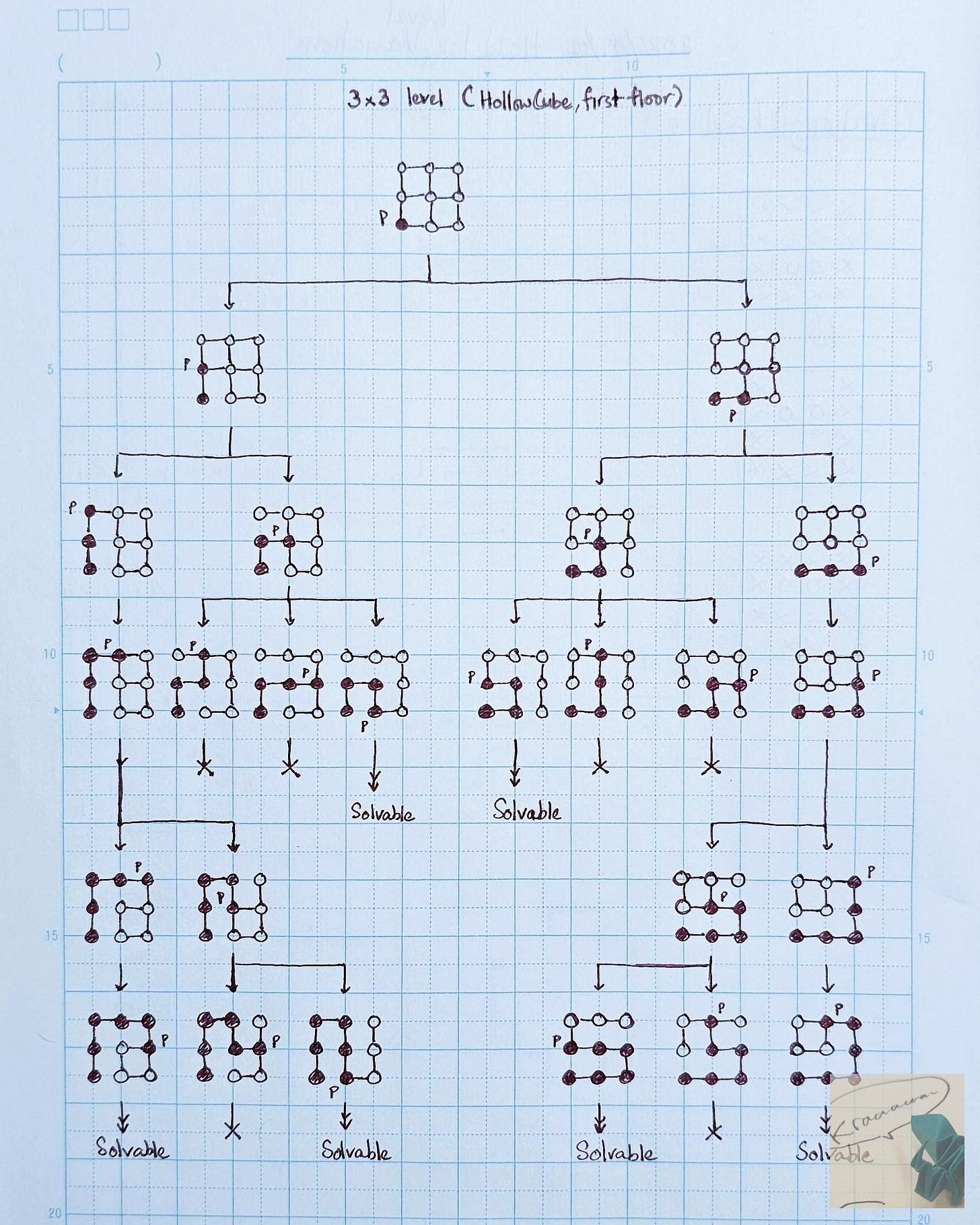

Now, let’s look at a larger puzzle - the first floor of Hollow Cube.

Our graph of game states quickly grows in complexity and number of branches but is still manageable to draw by hand.

Notice that not only can we recognize branches where the solution is trivial, but we can also recognize preceding moves that always lead to a game over (marked as branches where the arrows end with an ‘X’).

Any move that splits the level shape into two areas always leads to a game over. Keeping this in mind allows us to eliminate these moves earlier in the branch before we get to the obvious game over state.

III.

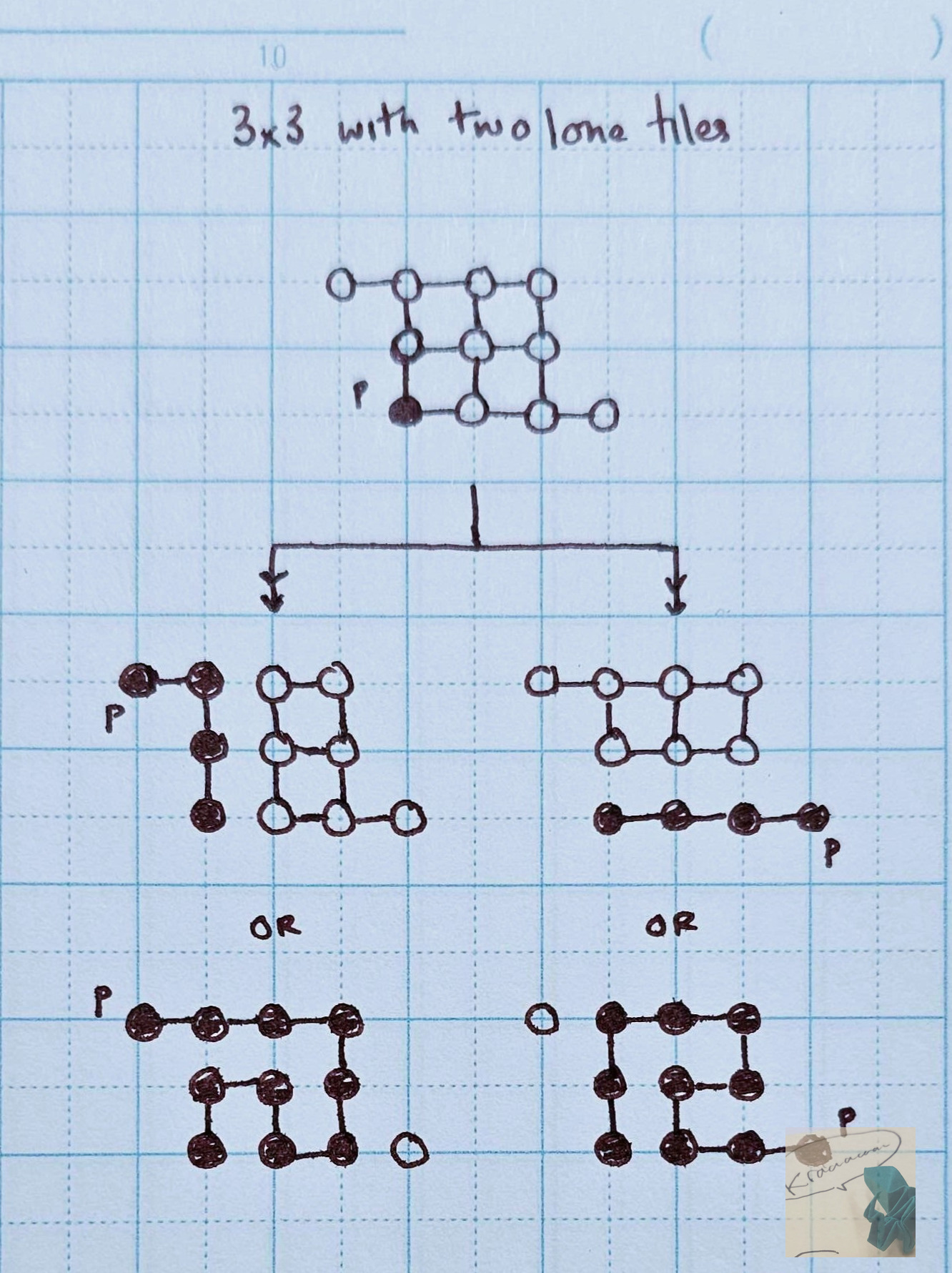

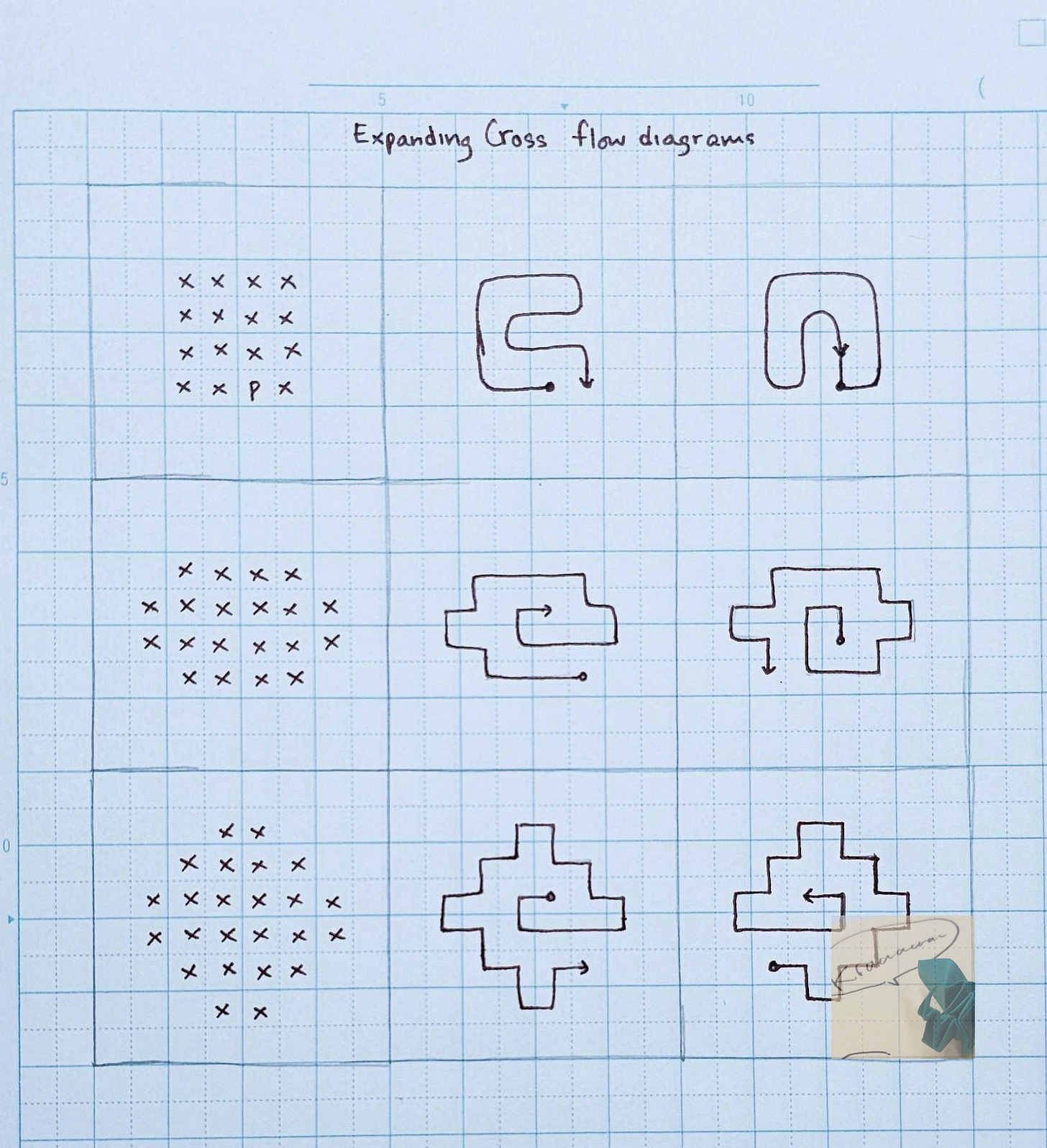

Let's look at another shape.

Observe that the lone tile on the upper left has only one connection to the rest of the tiles. This means that once you step on it, you can't go back and access any of the other tiles in the shape. So, we must end on this tile. In fact, this shape is unsolvable because we have a second 'lone' tile on the lower right side of the level.

We can only solve this shape if we start at one of the lone tiles -and we must end on the other one. This becomes important in levels like Bowtie (or Stackem or Candy Canes), because you must complete the previous floor and aim to land on the lone tile below.

IV.

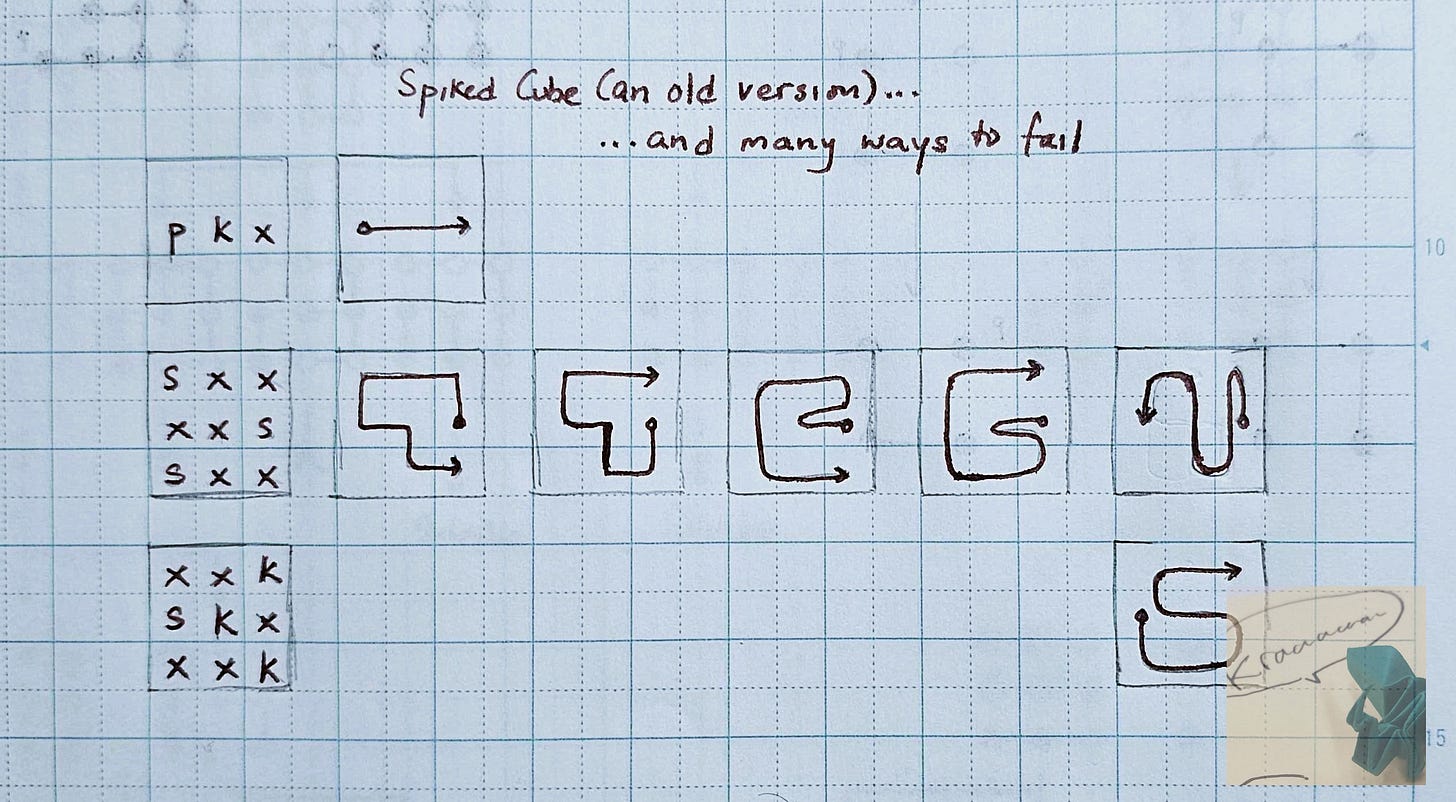

Visualizing each puzzle as nodes+lines (edges+vertices), systematically considering the available moves at every step, and pruning the options that lead to unsolvable states is how I approach solving our levels. It is also how I visualize designing our levels. I skip the nodes and lines and directly draw the flow lines I want the player to take on a level. Then I exhaustively analyze every possible path the player could take through the level.

Allowing multiple paths to solve the level makes for easier puzzles. To make a harder puzzle, I aim to cut off some paths in interesting ways that could hint at the intended solution or in fun ways to fail (for example, bouncing off consecutive trampolines or falling through a hole).

V.

Often the flow of motion informs the shape of my levels. In 3 turns, I wanted to approximate the motion of a 3-turn in ice skating.

But of course, the player has the freedom to solve the puzzle in other flows, and our puzzle design must account for majority of them to feel satisfying.

Early on during our development I was curious about writing a program to test solutions for our puzzles. The intention was to speed up our design process by quickly testing if a shape was solvable or not. I'm glad we set a time limit for working on that dev tool. Line puzzles are essentially variations on the Traveling Salesman problem and that problem is a well-known NP-hard problem. Celebrated mathematicians and smarter folks than I have tackled this problem and proved there is no trivial way to solve this problem. Which makes sense - if there was a trivial approach to these puzzles, we thinky-gamers wouldn't enjoy the process of scratching our brains till we solved them!

You can play Skadi Tower on iOS and Android.

We're working on a content update with fresh levels and a new tile mechanic. Please look forward to it soon.

Chase, W. G., & Simon, H. A. (1973). Perception in chess. Cognitive Psychology, 4(1), 55–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/0010-0285(73)90004-2.

Coach Julia. "How To Do A Forward Outside Three-Turn In Figure Skates." YouTube, uploaded 2 Aug. 2020, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=njqJC85X8U0.